The southern boundary of Charleston is fortified by a structure known as The Battery, a venerable seawall constructed to protect our fair city from incursions both tropical and military.

The Battery has undergone a number of rebuilds and revisions over time, the product of which has resulted in the distinctive shape of the Charleston peninsula.

Moreover, The Battery also provides a vantage point for overlooking the nonchalant goings-on in Charleston Harbor.

Exploring the homes on The Battery is to travel through a bit of architectural history, beginning with the earlier homes that developed as a southern extension to East Bay Street.

Behind Revolutionary War era fortifications we call the High Battery, this extension was named East Battery Street. It’s behind this seawall that opulent estates from the 18th and 19th centuries are among the architectural crown jewels of Charleston.

White Point Garden began to take shape around this time, and then a Low Battery was constructed that laid foundations for the distinguished homes that grace Murray Boulevard.

Each brick and cobblestone narrates a story of Charleston’s past, inviting you to become a part of its living legacy.

It’s the most iconic structure in the city, a promenade from which to appreciate the entirety of our history and culture: The Battery in Charleston defines the boundary of the city, while providing a full panoramic of its place in the Lowcountry.

The experience of The Battery in Charleston is a linear walkway on the southern perimeter of the Historic Charleston peninsula. Strolling past the homes and structures of East Bay Street gives way to East Battery Street, defined by stately antebellum mansions overlooking the Charleston Harbor. This portion is known as the High Battery, a substantial seawall that functions to buffer the city from high tides and tropical storms.

A few steps further one lands upon White Point Garden, a six acre public park occupying the southernmost point of Charleston, and one of the most photographed scenes in the southern United States.

Homes of The Battery

The High Battery

Recent Sales:

The Low Battery

Recent Sales:

White Point Garden

Recent Sales:

History of The Battery

Colonial Defense

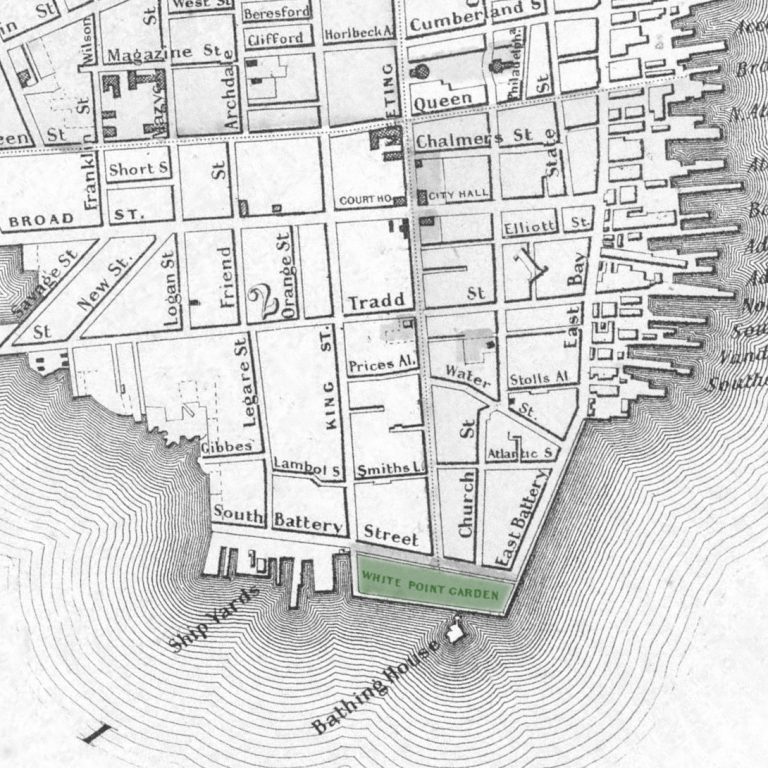

From its founding in 1680, the provincial city of Charles Town established mostly on the high grounds of what is now the French Quarter and South of Broad, southward to the banks of Vanderhorst’s Creek (modern day Water Street).

Beyond this creek was a sandy shoreline known as White Point, for its expanses of oyster shells deposited among the tide-lashed beach.

In the 1720s, the provincial government of South Carolina sought to establish a barricade on the southern end of the peninsula, beginning with the installation of simple wooden pilings flanked by ballast stones.

By the next decade, Charles Town made its first expansion into the harbor, extending Church Street over Vanderhorst’s Creek, terminating with a new brick fortification known as Broughton’s Battery.

A double row of wood pilings in the sandy beaches of White Point extended westward to Council Street, and the first iteration of a southern seawall in Charleston began to take shape and define the southern boundary of the provincial town.

As a European war broke out in the 1740s and spilled over to the colonies, the Charleston battery was fortified with earthen ramparts around White Point and several cannons on Broughton’s Battery. The pilings and bulwarks remained a few years after the end of what the colonists termed King George’s War, but were largely destroyed by a powerful hurricane in September of 1752.

Seeking a more permanent seawall to fortify the southern peninsula and protect from attack, a far more substantial system of ramparts were built in the 1750s. These earthen walls were still susceptible to the forces of nature, and by the late 1760s a brick wall was constructed to protect them, five feet high and backfilled – permanently raising the beach of White Point. Banks of cannons were installed to protect the city, and by 1769 the brick wall a half mile in length rose above what was once the beaches of White Point.

By this time tensions were rapidly accelerating between the colonies and Great Britain, and by the time the Revolutionary War kicked off in 1776 the battery in Charleston was thoroughly militarized with defensive cannons behind parapet walls.

Developing Real Estate

It was the dawn of a new era in the 1780s for the freshly established United States. Following three unpleasant years of British occupation, the City of Charleston was liberated and incorporated in 1783.

Wartime fortifications on White Point were mostly dismantled, along with the half-century old ramparts and pilings.

The City of Charleston embarked upon an ambitious plan to expand the area around White Point for southward development of the city: a sixty-foot-wide promenade enclosed by a robust new seawall. A complicating factor: the seawall must be constructed entirely within the waters of the Cooper River.

Fortunes were not on the side of the construction efforts that commenced in the 1790s, as the hurricane of 1797 destroyed the entire project. After starting again the next year, the hurricane of 1800 came along to again destroy the project. A revamped plan to employ brick walls instead of palmetto logs commenced the following year, but even this was totally destroyed by the hurricane of 1804.

The plan for The Battery was again overhauled, this time with more durable materials: granite blocks. Following a decade of construction – even during the War of 1812 – the High Battery much as we know it today was complete by 1818, enclosing acres of new vacant land in the South of Broad neighborhood from the Cooper River.

The wide promenade became an extension of East Bay Street, and would come to be known as East Battery Street. Throughout the first half of the 19th century, grand homes were constructed on East Battery Street in lavish opulence.

The Battery remained much the same until the hurricane of 1854, after which the seawall was raised to its current height.

This structure, which we call The High Battery, remains in place today.

White Point Garden

By the 1830s Charleston decided the best use for much of the new land behind The Battery would be a grand public park, the city’s first.

A wharf wall of palmetto logs built up the southern end of the peninsula from the High Battery to Meeting Street, and additional earth was brought in for backfill along with plantings to create a green space about half the size of the current park.

By 1852 Charleston had enclosed White Point Garden with a seawall of more durable granite materials that composed the High Battery constructed years earlier, and nearly doubled its size with an extension to King Street.

While much of the newly created land behind the High Battery remained vacant, by 1860 a number of homes were built adjacent to White Point Garden during this era, along South Battery Street.

The Low Battery

The current occupants of that land were a number of wharves and shipyards that were generally frowned upon as unbecoming of such an otherwise beautiful promenade. The city made moves to purchase this land, and was initially successful with some parcels – including the site that is today the Fort Sumter House.

Despite best laid plans, several legal snafus and then a devastating Civil War ground this process to a halt for decades.

Needless to say, Charleston experienced a half century of economic ravages and shifting priorities for its infrastructure. However by the 1900s city leaders began to revisit the idea of extending The Battery westward into the Ashley River.

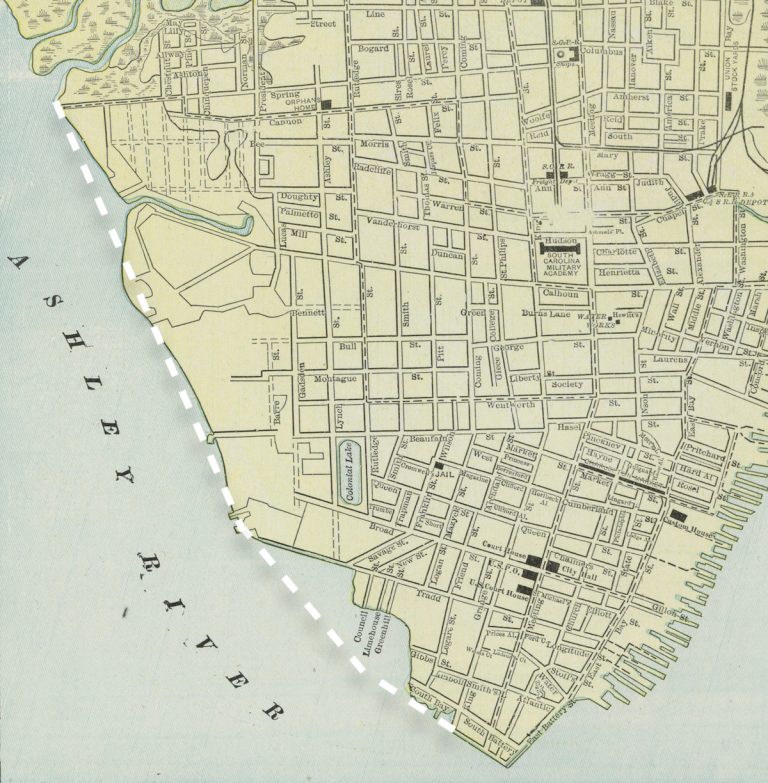

The idea for The Boulevard Project was bold: a new seawall extending from White Point Garden into the Ashley River to Tradd Street, and then extending up the Ashley River all the way to a proposed bridge at Spring Street in Midtown.

The project was to be completed in stages, with the ambition of eventually reaching as far north as Hampton Park.

The transformation of the Ashley Riverfront would be dramatic.

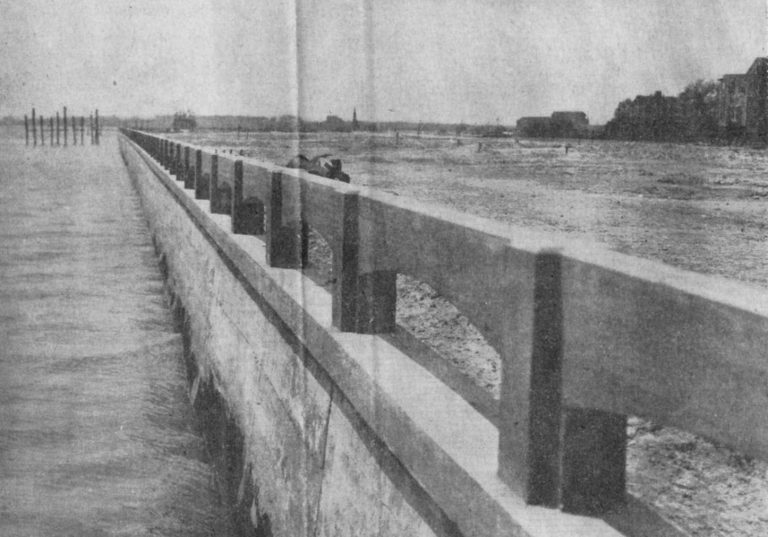

The Low Battery is named such as its height was built lower than the original East Battery, which buffers the brunt of tropical storms.

The first phase of the Boulevard Project extended from White Point Garden to Tradd Street.

The city broke ground in 1909 on a new seawall nearly 4,000 feet in length that would be backfilled to create an entirely new waterfront neighborhood in South of Broad.

Ultimately this first phase was the only phase, and our Low Battery terminates at the U.S. Coast Guard Base Charleston on Tradd Street.

The Low Battery seawall was completed in 1911, and once dredging from Charleston Harbor produced 667,000 cubic yards of fill behind the seawall, there was a whopping 47 acres of new buildable land, much of it waterfront. Once parceled, the South of Broad neighborhood gained 191 new residential lots.

Atop the seawall was a promenade paved in oyster shells, as were several of the new streets.

The oyster shell surface quickly disappeared into the newly filled mudflats, until a local resident – Andrew Buist Murray – donated funds to have the street properly paved.

The waterfront street along the Low Battery has since been named Murray Boulevard, and wraps around White Point Garden to join East Battery Street.

– Homes for Sale –

The Battery in the 21st Century

The seawalls that define the southern perimeter of the Charleston peninsula were designed in different eras – the High Battery in the 19th century, the Low Battery in the 20th – though now we are facing a new set of challenges that require a rethinking of those iconic structures.

The current leaders of Charleston are examining the condition of the seawalls and what needs to be done to maintain or rebuild them.

Of particular concern is the height of The Battery as we observe rising sea levels and intensifying tropical storms.

In the coming years we will have some tough decisions ahead of us as we look to modernize The Battery for these new challenges, and we look forward to participating in that dialogue.